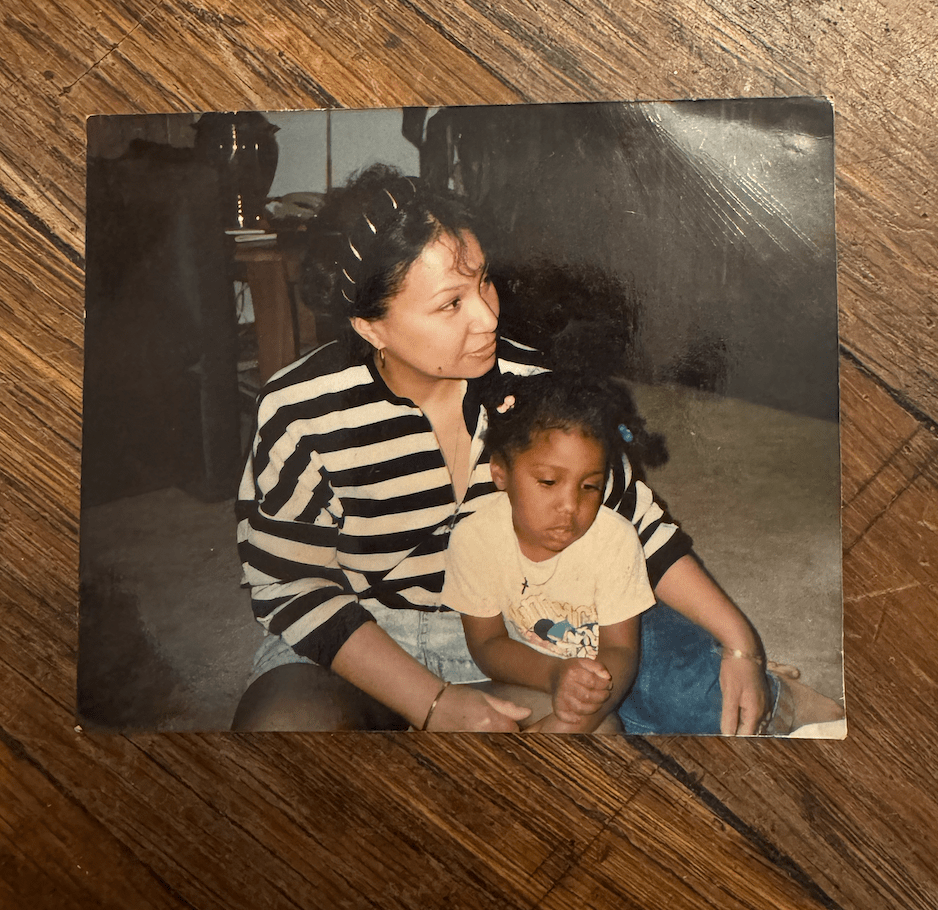

I woke up because something was different. I was 5 years old, and as far as I could remember, my mom had been there when I woke up. I didn’t have my own room until I was about 10. The room was in the back corner of the railroad style house. When you walked out of the bedroom, there was another room to walk through before you were let out into the dining room. It wasn’t a big house. I took two steps into the dining room and looked left into the kitchen archway like there was a yield sign. The kitchen is small, and you don’t have to walk all the way into the room to see the back door leading out to the yard. Ignoring the invisible yield sign, my sister emerged from the kitchen. For the record, all the invisible signs in the house were for me, but they weren’t all created by me.

“Where’s mom?” I asked her and she was immediately irritated. Since the minute I met my sister, she’s been the same person. She is the most determined and responsible person I have ever met, to a fault even. She always has something better to do.

“I don’t know,” she replied, and I supposed I had already learned not to engage her in conversation she doesn’t want to have. I turned my head to the right; I could see my brother through the window, walking up the stairs to the front porch.

“Where’s mom?” I repeated.

“I don’t know,” he answered but brushed me off and kept walking into a hallway closer to the front door.

Does anyone know anything? I asked myself.

I stood still and watched until my brother returned. Since the minute I met my brother, I looked to him like he had all the answers. For reasons I can’t explain, I respected and admired every breath he took & I tried my best to have a character he would approve of, even if he didn’t like it. I never thought my brother was perfect, but I always thought he was fucking amazing.

When he returned, he was carrying a big black bag and walked straight out the front door. From across the room, I watched through the window as he walked down the front porch steps. I don’t remember him coming back. My memory actually just changes scenes at that point. The next thing I remember, they were gone, too.

• • •

I’m not sure if it was the same day or the next day. It’s just the next thing I remember. If you’ll remember… I was 5.

We were sitting on the steps in the backyard which are a humble 3-4 steps made of concrete, and they’ve never had railings. To the right of the stairs was a short concrete path leadin to a chain link fence that opened into the narrow driveway. To the left, a matching concrete path allowing for a cellar door. I’m not sure what was further to the left, but 30 years later, there’s a beautiful deck my mom worked on since I was a teenager. When I was 5, it must have been the same patchy grass and dirt as the rest of the yard. We sat there together, guarding each other and the dirt my dad left us.

Negrita, my dad’s Black lab, was sitting to my right, on the stairs with me. She was the reason the yard didn’t stand a chance — by way of old-school pet keeping. We kept her on a chain & the links got heavier and heavier every time she bit or broke through it. That dog never growled at me once, but she did get out on me once and chase someone onto the roof of a car. No one dared come into our yard, let alone our home, with Negrita on guard. She was my kind of vicious & very necessary for a 5-year-old girl left alone.

“Everything’s gonna be all right,” I told Negrita. I decided that I knew how to read and write, how to dress and wash myself, and how to make ramen (I liked beef with sliced hot dogs), therefore, we could make it. My mother’s friend, [we’ll call her] Doña Colombia, moved into our house and became my guardian.

• • •

I’m thankful for Doña Colombia’s lack of affection; I learned early that people aren’t obligated to love you. I also learned how to coexist with people I do not care for by ignoring their existence completely. On the other hand, Doña Colombia’s daughter loved me like her mother would never love either of us. She took me everywhere; I even walked in the Colombian Parade.

Doña Colombia worked in a factory where they’d work on huge machines rolling yards of fabric onto different types of tubing. I’d sometimes go to work with her and put barcode stickers on the ends of the reams. Sometimes, I’d make $5.

When Doña Colombia went on vacation, she’d leave me where she needed to. My least favorite was at my mom’s ex-boyfriend’s sister’s house (you read that right) in the only projects we had nearby. I wasn’t scared or treated poorly; I just didn’t know those people.

My favorite place was at La Verdadera Doña’s house (whole other Colombian lady), and everyone knew she ran the entire city. [Side Note: Don’t do or sell drugs, Kids.] I love a woman in charge. La Verdadera Doña did hair, and she worked in jewelry. We put earrings into packaging when I stayed at her house. (I never made a dollar for that.) My work in fashion technically started earlier than I can usually tell people.

Monet Jewelry specifically elicits a core memory for me because the factory was right at the exit to my city. Last I saw it was a U-Haul storage, & they’ve even changed the exit number since then. Central Falls, Pawtucket, and Providence are where most of the underserved of Rhode Island reside. We are at the heart of New England, which has veins and arteries made of rivers and streams that are filled with factories (mostly just their shells now, since many have become lofts). Interstate 95 cuts right through the forgotten, previously industrialized state, making it a great place to just “pass through” or ultimately hide out. Central Falls, has a pretty large Colombian population and that’s why I know so much about arepas, chorizo, empanadas and the drug trade.

Putting earrings on those fancy Monet holders at La Verdadera Doña’s kitchen table feels like a memory from another time, but it could have been yesterday. I knew exactly who she was, and I somehow knew I shouldn’t be at her house. For a moment, I felt like a real grown-up lady. After I finished enough jewelry, I’d go outside and play pogs. Child labor, schmild labor. Years later, my mom told me she did her time instead of giving names because she wanted to keep us safe. Meanwhile, I was playing pogsin the lion’s lair.

• • •

While my mother found a way for me to stay in my childhood home (another story for another time), my brother and sister were separated and had to stay with different aunts and uncles in Upstate New York. My sister isn’t the type to divulge much. I wish I could have asked my brother more, but he passed away in 2006. Still, my brother was the type to tell the truth but didn’t want to hear it.

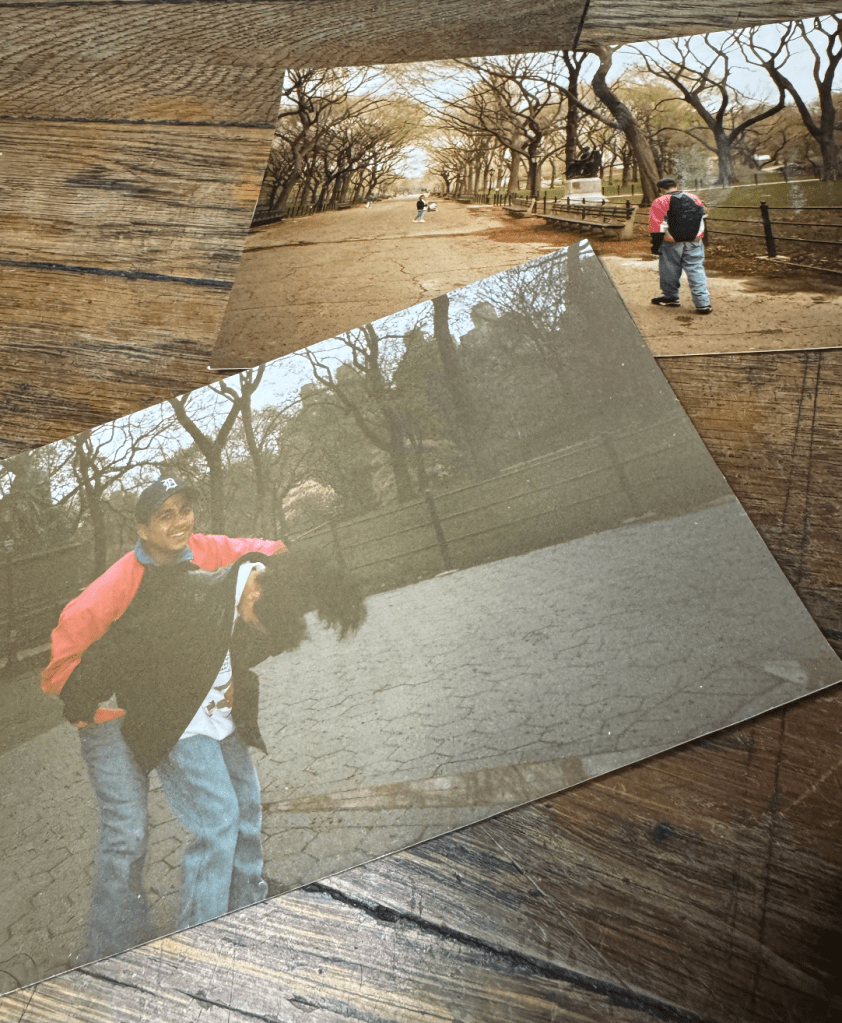

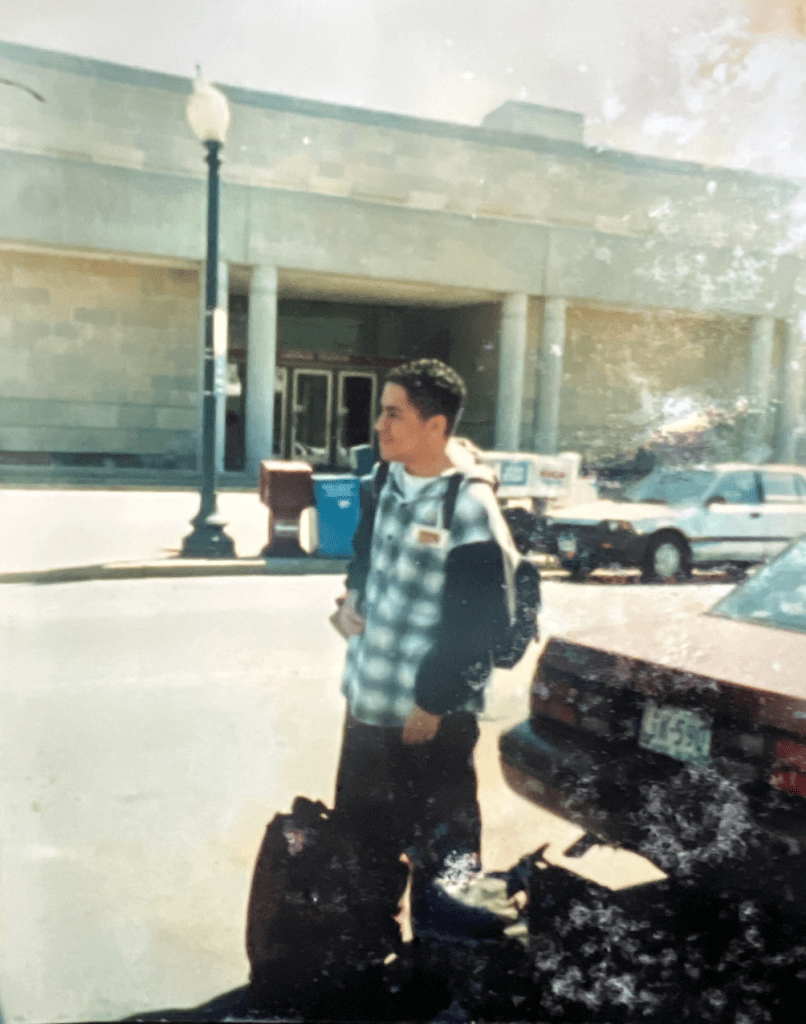

I only know bits of what my siblings went through, and I know little of it from them, so I can only write my story from my perspective. Years later, I found a picture of my brother standing outside the train station with a big black bag. My mom says that’s the day he left. I intend to write these chapters with trust in myself as well as my memories, although I know both are biased and flawed.

My introduction to the world was a lone existence in which I had little control and little information, but I found out what I could and made the most of the autonomy I could find. My mom’s disappearance feels like my first memory, but it’s simply the moment I stopped being a child. I’m grateful for the early years I don’t remember — I must have felt safe. For the next two years, I saw my mother and siblings once or twice each, my mother only once for sure. My sister loves to send a care package, but my brother was a teenage boy and hard to reach on a calling card. My mom asked for letters, but also told me to make the stamps last. Negrita got sick, and Doña Colombia lied to me about it. I waited for weeks for my dog to come back home and then realized I was really out here alone.

• • •

It was the 90s and TV was great but we still played outside. I knew all the kids next door and their parents. I read a lot of books. I lost and found myself in writing – from letters to my family and school projects to diaries I’ll have to burn before I die.

I loved to write. I’d go across the street to Lori’s house and get a stamp so I could send a letter to my mother. Lori was one of my brother’s ex-girlfriends… actually, I don’t know if they dated, I just know they loved each other – my childish heart could feel it. Years later, she was among the few I was glad to see at my brother’s funeral.

My brother dated some amazing women, although I learned from the ones I liked and the ones I didn’t. (More stories for more times). The one time we visited my mom, Doña Colombia said I was spending too much time at Lori’s house. But Lori was buying me stamps and helping me correct my spelling.

I felt like I already knew so many things by the age of 5. Most importantly, I knew my mother’s address, & eventually, I understood where she was: Danbury Correctional Facility in Connecticut. I was taught to say she was “on vacation” / “de vacaiones,” which sounds like an even bigger lie in a Colombian accent. My mother was in a cage, 2.5 hours from me, and I only saw her once.

I’d have to wait over a decade to find out is why my mother was incarcerated in the first place. I’d wait an additional decade to find out why my father was the blessing she painted him as, but just as much a problem.

I’ll introduce you to my dad in the next chapter.

Leave a comment